Anatomy of Story

_13

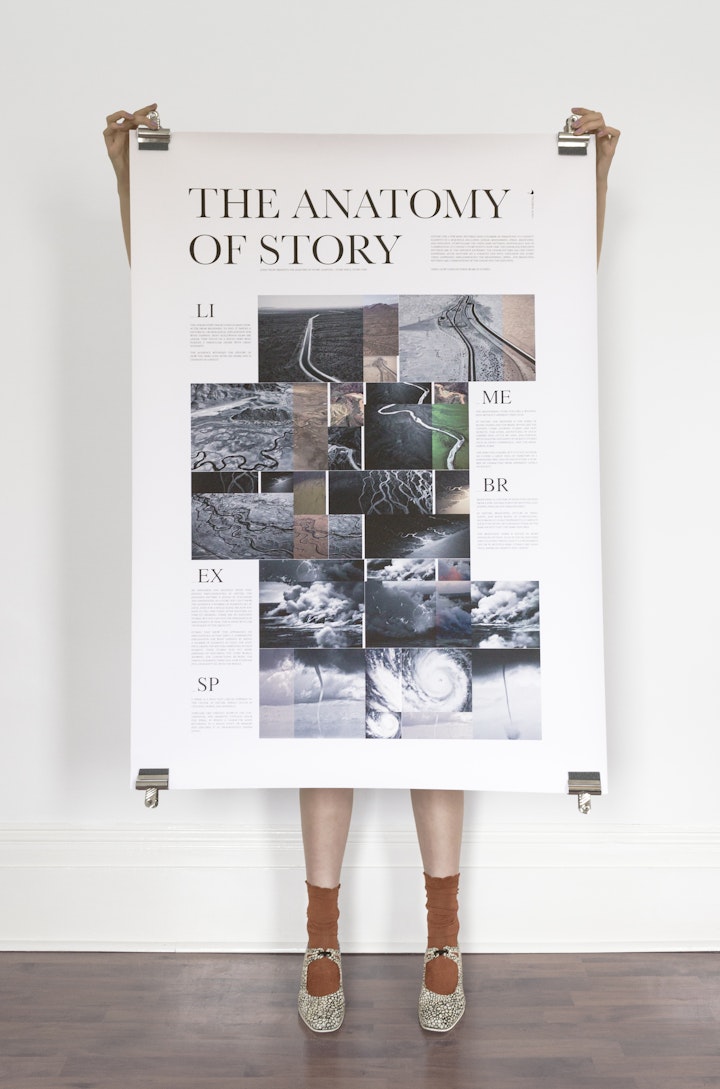

The Anatomy of Story is a masterclass in scriptwriting for film by screenwriter John Truby. In the introductory chapter of his book Truby illustrates five story arcs, likening them to natural processes and elements. They are as follows:

Linear Story

The linear story tracks a single main character from beginning to end.

It implies a historical or biological explanation for what happens. Most hollywood films are linear. They focus on a single hero who pursues a particular desire with great intensity. The audience witnesses the history of the how the hero goes after his desire and is changed as a result.

Meandering Story

The meandering story follows a winding path without apparent direction. In nature, the meander is the form of rivers, snakes and the brain.

Myths like the Odyssey; comic journey stories like Don Quixote, Tom Jones, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Little Big Man, and Flirting with Disaster; and many of Dicken’s stories, such as David Copperfield, take the meandering form. The hero has a desire, but it is not intense; he covers a great deal of territory in a haphazard way; and he encounters a number of characters from different levels of society.

Branching Story

Branching is a system of paths that extend from a few central points by splitting and adding smaller and smaller parts.

In nature, branching occurs in trees, leaves, and river basins. In storytelling, each branch usually represents a complete society in detail or a detailed stage of the same society that the hero explores. The branching form is found in a more advanced fiction, such as social fantasies like Gulliver’s Travels and It’s a Wonderful Life or in multiple-hero stories like Nashville, American Graffiti, and Traffic.

Explosive Story

An explosion has multiple paths that extend simultaneously; in nature, the explosive pattern is found in volcanoes and dandelions.

In a story, you can’t show the audience a number of elements all at once, even for a single scene, because you have to tell one thing after another; so, strictly speaking, there are no explosive stories. But you can give the appearance of simultaneity. In film, this is done with the technique of the cross cut.

Stories that show (the appearance of) simultaneous action imply a comparative explanation for what happens. By seeing a number of elements at once, the audience grasps the key idea embedded in each element. These stories also put more emphasis on exploring the story world, showing the connections between the various elements there and how everyone fits, or doesn’t fit, with the whole.

Stories that emphasize simultaneous action tend to use a branching structure and include American Graffiti, Pulp Fiction, Traffic, Syriana, Crash, Nashville, Tristan Shandy, Ulysses, Last Year at Marienbad, Ragtime, The Canterbury Tales, L.A Confidential, and Hannah and Her Sisters. Each represents a different combination of linear and simultaneous storytelling, but each emphasizes characters existing together in the story world as opposed to a single character developing from beginning to end.

Spiral Story

A spiral is a path that circles inwards to the centre.

In nature, spirals occur in cyclones, horns, and seashells. Thrillers like Vertigo, Blow-Up, The Conversation, and Memento typically favor the spiral, in which a character keeps returning to a single event or memory and explores it at progressively deeper levels.

This poster was produced and printed for Chris and limited to 4 archival copies. John Truby’s Anatomy of Story is available from his website.